Post-Apocalyptic Push and Pull Factors

When we analyze human migration we are analyzing how people move. To do this, we need to look at some of the reasons people move. This is where the theory of push and pull factors comes in handy. Push factors are reasons to leave a place and pull factors are reasons to go to a place.

© Telltale Games

Interestingly enough, Lee Everett is a character in The Walking Dead’s Telltale Games mobile game. Both Lee Everett and Everett Lee also taught at University of Georgia.

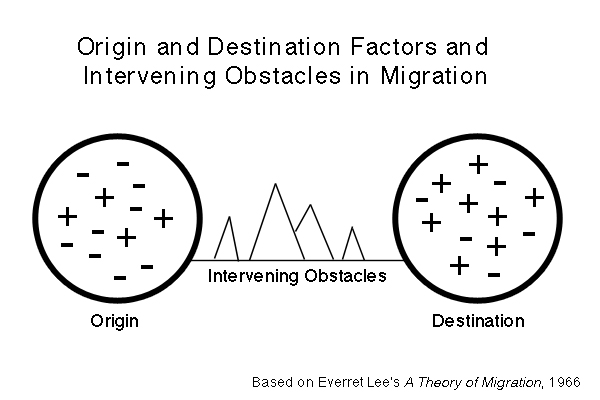

The model behind push and pull factors was developed by a professor named Everett Lee. He published his theories on push and pull factors in an article called A Theory of Migration in 1966. In this article, he defined push and pull factors and provided examples of both. He noted that push and pull factors may be different for different people. Lee (1966) described an example with the following:

Thus a good climate is attractive and a bad climate is repulsive to nearly everyone; but a good school system may be counted as a + by a parent with young children and a – by a house- owner with no children because of the high real estate taxes engendered, while an unmarried male without taxable property is indifferent to the situation. (p. 50)

In this quote, we see that a pull factor for one person could be a pull factor for another person. This is an important idea to keep in mind. Just as push and pull factors may be different for different people, push and pull factors may change in a post apocalyptic setting.

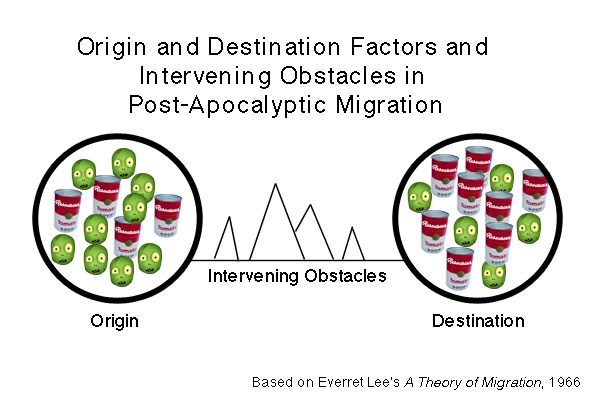

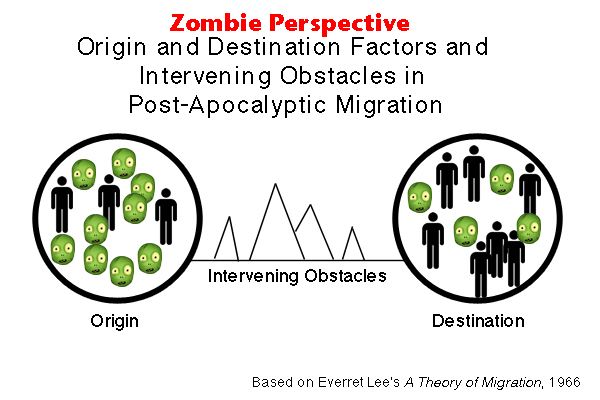

In Lee’s model, positive (pull) and negative (push) factors as well as intervening obstacles play a role in the choice to move.

Notice the diagram of the push and pull factors in a post apocalyptic scenario. Zombies are probably a push factor for nearly everyone. Food and resources would be a pull factor. However, we must keep in mind the push and pull factors of zombies. It is probably safe to assume that zombies will be pulled to a location that has more humans (zombie food).

By considering the movement of zombies and other humans, it would be possible to stay a few steps ahead of everyone else. Before migrating to a new location, consider possible migrations of other humans and zombies. Determine if you will be ready to deal with these other migrations.

Lee, E. S. (1966). A theory of migration. Demography, 3(1), 47-57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2060063